“Group unveils initiative to reinstate out-of-school children in northern Nigeria – Punch https://punchng.com/group-unveils-initiative-to-reinstate-out-of-school-children-in-northern-nigeria/Newspapers”

https://www.vanguardngr.com/2025/11/faith-leaders-urged-to-champion-child-education/

https://leadership.ng/group-unveils-platform-for-returning-500-children-to-school/

https://www.facebook.com/share/p/17UPiWd8sg

Keynote Address on the Inauguration of Lihdi VisionCasting & Fundraising Symposium29th November, 2025.At Unity Hall, National Institute for Policy and Strategic Studies (NIPSS), Kuru, Jos.

Theme: Restoring Learning, Rebuilding Lives

Topic: Insight into How Culture and Indigenous Values Can Motivate Families and communities to Support Education for Every Child

Speaker: Pastor Yakubu Samuel Nzee, PhD

Occasion: Mobilization gathering for reintegration of out-of-school, crisis-affected children (North-West, North-East, Middle Belt)

Target: Faith-based, cultural, and social actors

Introduction

Honourable Guests, Faith Leaders, Cultural Custodians, Community Elders, Social Activists, Esteemed Colleagues, ladies and gentlemen:

I greet you in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ, whose heart for children is expressed throughout Scripture. I thank you for coming together under this noble banner of La Iris Human Development Initiatives (LIHDI): having the goal of “Restoring Learning, and Rebuilding Lives.”

We are gathered for a weighty but hopeful mission: to reintegrate 500 crisis-affected children (aged 5-17) from our North-West, North-East, and Middle Belt regions back into school to offer them the dignity of learning, the hope of a future, and the chance to fulfil their God-given potential.

But as we know, schooling is not only about classrooms and textbooks. It is deeply embedded in the social system in family decisions, in community values, in culture, and in worldview. That is why today’s topic is so vital: “Insight into how our culture and indigenous values can become sources of motivation for families and communities to support education for every child.”

I speak to you not only as a social mobilizer or community planner, but with a

theological conviction rooted in African Christian thought. I draw on the insights of African theologians Yusufu Turaki, Samuel Waje Kunhiyop, and Sunday Bobai Agang to offer a foundation for our collective work.

My hope is that by the end of this address, we will not only be inspired, but also be

better equipped with theological, cultural, and practical clarity to mobilise our

communities for this critical work of educational inclusion.

I. Theological and Conceptual Foundation

The Social System: Why Culture Matters

To mobilize communities, we must engage not just individuals, but social systems, the networks of relationships, beliefs, values, and institutions that shape daily life. This is precisely the kind of holism called for in the work of the Dist. Professor Emeritus, Yusufu Turaki. In his Engaging Religions and Worldviews in Africa: A Christian Theological Method, Turaki argues that African theology must take the social realities, cultural heritage, and worldview of African peoples.1 Turaki’s method challenges any theology that divorces faith from context. For him, to do theology in Africa means to

acknowledge the weight of traditional worldviews, yet to subject them to biblical critique and Christian redemptive transformation.2 In practical terms: if we want to mobilize communities to support education, we must start with their social ontology, the web of communal relationships, cultural norms, and indigenous values that shape how they think about children, responsibility, and the future.

The Role of the Church and Public Theology

Education for out-of-school children is not merely a social development task; it is a matter of justice, human dignity, and Christian responsibility. This is why we need what Sunday Bobai Agang calls an African Public Theology, a theology that refuses the sacred-secular divide and applies Christian faith to public life, society, culture, and development. Agang and his collaborators argue that Christians must engage issues such as education, poverty, health, and civic life not as optional social services, but as integral to their calling as disciples. Thus, when we mobilize for the schooling of crisis affected children, we are not performing a charitable add-on; we are enacting theology,

living out God’s purpose for the community, affirming human dignity, and pursuing the common good.

Contextual Theology and African Christian Theology

Our effort finds further grounding in the work of Samuel Waje Kunhiyop, especially his African Christian Theology. Kunhiyop contends that Christian theology for Africans cannot ignore African worldviews, spiritual experiences, traditional values, or indigenous understandings of life, death, community, and destiny. He argues that because African Christians come from traditional religious backgrounds, their worldview, even after conversion, continues to shape their understanding of God, humanity, morality, suffering, destiny, and social life. An African Christian theology, therefore, must mediate between biblical faith and African culture in a way that is faithful to Scripture an relevant to lived experience.

Therefore, when we appeal to culture and indigenous values to support education, we are not compromising the gospel, but participating in the “incarnational” task of expressing Christian faith within African social realities.

II. Indigenous Values as Motivational Resources for Education

Rooted in this theological and conceptual foundation, let us now explore several indigenous values deeply embedded in African cultures, especially in the regions we serve (North-West, North-East, Middle Belt) and reflect on how they can become powerful motivators for supporting education.

- Communal Responsibility and Collective Child-Rearing

Across many African societies, the raising of a child is a communal endeavour. The adage “It takes a village to raise a child” is not a cliché; it is a lived reality. Family extends beyond parents to uncles, aunts, grandparents, neighbours, clan members, and elders.

In such a system, the education of a child is not simply a private family matter; it is a communal investment. When a community invests in educating one child, it invests in the future of the whole group.

By appealing to this communal responsibility, faith leaders, traditional rulers, and social actors can mobilize widely: neighbours help pay fees, elders offer mentorship, community groups provide support for books or uniforms, and cultural associations commit to “adopt” children whose schooling was disrupted by crisis.

This use of communal values echoes Turaki’s insight that African social systems, when rooted in Christian ethics, can be harnessed for the common good. - Culture, Indigenous Values, and the African Social System

African theologian Yusufu Turaki, in his work on African social systems, argues that African communities are deeply shaped by communalism, moral order, and the sanctity of relationships. These communal systems, he explains, are sustained by shared values, collective responsibility, and social solidarity.

This means that in African thought:

i. A child does not belong only to the parents,

ii. A child belongs to the entire community,

iii. And every adult bears moral responsibility for their well-being and growth.

This principle aligns naturally with education. In Turaki’s words, African social ethics are built on “the corporate responsibility of the community for the individual.” If embraced today, this indigenous ethic can inspire communities to ensure that no child remains outside the reach of learning, especially those displaced by conflict. Turaki’s framework suggests that the reintegration of out-of-school children is not merely a governmental task; it is a communal obligation born out of African identity itself.

This is how this diagram works and its value in social research and inquiry.

Four Basic Social Variables in a Social System

Values in a Social System

Beliefs, Ideas, Traditions, Customs, Philosophies, Theologies, etc. - Structures in a Social System

Institutions, Organizations, Forms - Networks in a Social System

Interactions, Relationships, Engagements - Persons in a Social System

Individuals, Classes, People Groups - Respect for Knowledge, Elders, and Moral Formation

In many African traditions, knowledge is revered, and elders, as custodians of wisdom, hold high esteem. This respect extends to spiritual knowledge, moral instruction, social norms, and communal memories.

When Christian educators and church leaders frame formal education as an extension of this respect for wisdom, not as foreign or Western, but as consistent with African honour for knowledge, they give it cultural legitimacy.

Through public theology, we can articulate that education is not only for worldly success, but also for moral formation, community leadership, and social transformation, all values deeply embedded in African cultural consciousness. This parallels Kunhiyop’s argument that African Christian theology must engage traditional beliefs and values, not discard them. - Oral Tradition, Storytelling, and Value Transmission

Much of African cultural life is shaped through oral tradition stories, proverbs,

folktales, and parables, proverbs passed down from generation to generation. These

narratives serve to transmit values, ethics, communal history, and practical wisdom.

We can adapt these traditional communication channels for our purpose. For example:

i. Share stories of individuals from our region who, through education, overcame

hardship, supported their families, helped their communities, or brought

positive change.

ii. Use proverbs and folk wisdom to underscore the value of learning (e.g., “A learned child is a seed of prosperity for the community”).

iii. Use drama, poetry, songs in local languages to communicate that education is not a betrayal of culture but its preservation and enhancement.

This approach is entirely in line with Turaki’s call for a theology that engages, rather than rejects, African worldviews and cultural expressions. - Dignity, Self-Reliance, and Social Contribution

Indigenous African values often prize dignity, industriousness, self-reliance, social standing, and the capacity to contribute to one’s family and community.

Education can be framed not merely as a pathway to individual success, but as a means of equipping children to contribute meaningfully to their communities: to uplift their families, preserve their cultural heritage, provide leadership, and restore social justice.

From a Christian social-ethics perspective (as in Kunhiyop and Agang), this aligns with the biblical mandate for human flourishing, stewardship, and justice. Education becomes a tool for empowering the vulnerable, restoring dignity, and enabling social transformation.

III. The Theological and Ethical Imperatives for Supporting Education

Having identified cultural resources, we must root our mobilization in theological and ethical imperatives. Three stand out: the inherent dignity of the child, communal stewardship, and justice & inclusion.

A. Human Dignity and Imago Dei

Christian theology declares that every human being is made in the image of God (imago Dei). Therefore, every child, regardless of social status, background, hardship, or displacement, bears God’s image and deserves dignity, respect, and opportunity.

Education is one of the primary means by which a child can develop God-given potential, grow in knowledge, wisdom, and character, and be equipped to serve God and community. Denying a child education, particularly because of crisis, poverty, or social neglect, undermines his or her dignity.

Thus, our work is not optional; it is a theological imperative. As Agang’s African Public Theology insists, the Church must engage in public life to uphold human dignity and fulfil God’s design for human flourishing.

B. Communal Stewardship and Responsibility

Our responsibility does not end at individual children; it extends to families and communities. As stewards of God’s creation, which includes human relationships and social systems, we are called to care for the social well-being of our neighbours, especially the vulnerable: orphans, displaced children, and those affected by crisis.

In many African cultures, the notion of communal stewardship is intrinsic. By

collaborating with cultural custodians, faith leaders, and community members, our support for children’s education becomes a shared responsibility, a living enactment of Christian love in community.

This perspective is deeply embedded in African Christian theology, which seeks not only personal salvation but communal transformation and social justice. Kunhiyop’s theology reminds us that faith must impact everyday life, social structures, and community values

C. Justice, Equity, and Inclusion

Many of the out-of-school children we hope to reintegrate come from contexts of crisis, displacement, poverty, or social marginalization. For them, access to education is not a luxury, it is a matter of justice.

Christian public theology compels us to strive for equity and inclusion. When we mobilize for their education, we advocate for the common good, affirm human dignity, and resist social structures that perpetuate inequality.

In this way, our project becomes more than a social programme; it becomes prophetic, incarnational, and redemptive.

IV. Strategic Framework: Mobilizing Faith, Culture, and Community for

Education

Inspired by the theological and cultural foundations above, I propose a practical strategic framework for achieving our goal of reintegrating 500 children. This plan brings together faith-based, cultural, and social actors in a unified, collaborative effort. - Engage Cultural Custodians and Traditional Authorities

a. Convene meetings with chiefs, elders, clan heads, and cultural

institutions to present the project, its goals, and its significance.

b. Ask for their endorsement, blessing, and public commitment to support

returning children to school, for example, by contributing resources,

identifying children, mentoring, or monitoring progress.

c. Use their moral and cultural authority to influence family decisions. - Mobilize Faith Communities

a. Encourage pastors, imams, and religious leaders to speak about

education in sermons, services, and community gatherings, not only as a

social good but as a Christian calling.

b. Establish church-based or interfaith “Back-to-School” campaigns, where

congregations raise funds, provide sponsorship, or provide school

supplies and uniforms for children.

c. Use faith-based youth groups, Sunday schools, and community

ministries to identify out-of-school children, track their reintegration,

and offer ongoing support. - Leverage Oral Tradition, Storytelling, and Indigenous Communication

a. Develop culturally relevant testimonies, dramas, songs, proverbs, and

folklore that highlight the transformative power of education, especially

for those who have overcome crisis.

b. Present real-life stories of successfully reintegrated children from similar

contexts to inspire families, communities, and church congregations.

c. Use local languages and idioms; involve traditional storytellers, youth,

and artists; partner with cultural associations. - Establish Community-Based Education Support Systems

a. Set up community schools, alternative basic education classes, or

bridging programmes via churches, mosques, or community centres.

b. Launch scholarship funds or “education solidarity clubs” within

communities to support fees, uniforms, books, and other needs.

c. Engage older youth and young adults as mentors, tutors, or “big siblings”

to younger children building community ownership. - Advocate Through Public Theology for Structural Support

a. Use public theology to call local and state governments, NGOs, and

international partners for resources: funding, infrastructure, teacher

placement, psychosocial support for crisis-affected children.

b. Frame education not as charity, but as a justice issue, the basic right of

every child, rooted in human dignity and social responsibility. This

echoes the call of African Public Theology for Christian engagement in

public life.

c. Encourage policies and programmes that remove barriers (poverty,

displacement, lack of documentation) and provide inclusive access to

education. - Ensure Long-Term Community Ownership and Sustainability

a. Monitor and support children after reintegration not only academically,

but also socially, emotionally, and spiritually.

b. Integrate programmes into existing community structures, church, youth

groups, and cultural associations so the work continues beyond initial

reintegration.

c. Regularly report and celebrate progress in community gatherings,

religious services, and cultural events, to maintain momentum and public

commitment.

V. Illustrative Narrative: A Possible Story to Mobilize Communities

Permit me to sketch a short, hypothetical but realistic story you might use in community gatherings, sermons, or campaigns to illustrate how cultural values and theology can come alive in support of education.

“From Displacement to the Classroom: The Story of Amina (or Musa)”

Amina is a 13-year-old girl from a community in the North-East, whose schooling was disrupted when her family was displaced by conflict. For nearly two years, she worked in the market, fetching water and selling small goods, contributing to her family’s survival. But even as she laboured, elders and neighbours would tell her: “Education is for town children, not for displaced ones.” Many believed she should stay at home. One

day, the local Imam, in his Friday sermon, declared: “Every child is a gift from Allah; if we have the means to send one back to school, we must do so even if that child was displaced. Education is not just for the privileged; it is a right.” Simultaneously, the community chief called a meeting, urging families and neighbours to support returning children to school, saying: “If we lose our children’s future, we lose our community’s future.”

The church, mosque, and cultural association came together. They contributed a small fund, provided Amina with a uniform and school supplies, and volunteered her older cousin as a tutor after school. Local youth painted the walls of a community hall to enable after-school classes for reintegrated children. Today, Amina attends 7th grade, dreams of becoming a teacher, helps her younger siblings with homework, and

encourages others in her neighbourhood to return to school. Her return did not come as charity, but as the fulfilment of communal duty, cultural respect, and faith-drive compassion.

This kind of narrative, rooted in our social reality, reflecting our values, and framed by

theology, can move hearts and mobilize communities in a way that statistics, reports, or

policy documents rarely do.

VI. Addressing Potential Challenges

We must also be realistic. Mobilizing culture, faith, and community for education will face obstacles economic hardship, psychosocial trauma from crisis, displacement, distrust, competing values, and resistance from families.

Here are some strategies to anticipate and respond:

i. Economic hardship: If families cannot pay fees, we must rely on community based scholarships, church/mosque funds, or local donors. We must frame education not as a cost, but as a communal investment.

ii. Psychosocial trauma: Many children affected by crisis may be traumatized, shy, or distrustful. We need to provide counselling, mentoring, and safe spaces within church youth ministries, community centres, or traditional healing settings.

iii. Cultural resistance: Some families may view formal education as “Western” or alien to their culture. Here, our use of oral tradition, local language, and cultural framing is vital: we must show that education does not erase identity; it rather empowers it.

iv. Sustainability and follow-up: Reintegrating children is not a one-off project, but a long-term mission. We must embed follow-up in community structures through youth groups, church programmes, ongoing mentorship, and community accountability mechanisms.

VII. Conclusion: A Theological, Cultural, and Social Call to Commitment

Dear listener, our task is not easy, but it is urgent and vital. The lives of hundreds of children, their dignity, their future, their hope hang in the balance. Yet, we are not powerless. We have God’s call, the resources of our cultures, the moral authority of our faith, and the strength of our communities. Therefore, I call on each of you, faith leaders, traditional rulers, cultural custodians, social activists, community members, to commit

today, in this gathering, to the following:

i. To adopt at least one out-of-school child in your circle, community, or

congregation, and support his or her return to school.

ii. To use your moral and cultural influence to encourage other families to do the same.

iii. To mobilize resources, time, finances, and mentorship within your networks to ensure that returning children are not only enrolled, but supported.

iv. To embed this initiative in your community institutions, church, mosque, youth groups, and cultural associations so that returning to school becomes a communal norm, not an exception.

v. To advocate publicly to local governments, NGOs, and donors for inclusive education, as part of a broader commitment to human dignity, social justice, and the common good.

References

Agang, Sunday Bobai. A Public Theology of Peace: The Church and the Struggle for a

Just Society in Africa. Carlisle, UK: Langham Global Library, 2020.

Kunhiyop, Samuel Waje. African Christian Ethics. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan,

Kunhiyop, Samuel Waje. African Christian Theology. Nairobi, Kenya: WordAlive

Publishers, 2012.

Mbiti, John S. African Religions and Philosophy. London: Heinemann, 1969.

Mbiti, John S. Introduction to African Religion. 2nd ed. London: Heinemann, 1975.

Nyerere, Julius K. Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism. Dar es Salaam: Oxford University

Press, 1967.

Nyerere, Julius K. Education for Self-Reliance. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer,

Turaki, Yusufu. Christianity and African Gods: A Method in Theology. International

Bible Society Africa, 1999.

Turaki, Yusufu. Foundations of African Traditional Religion and Worldview.

WordAlive Publishers, 2006.

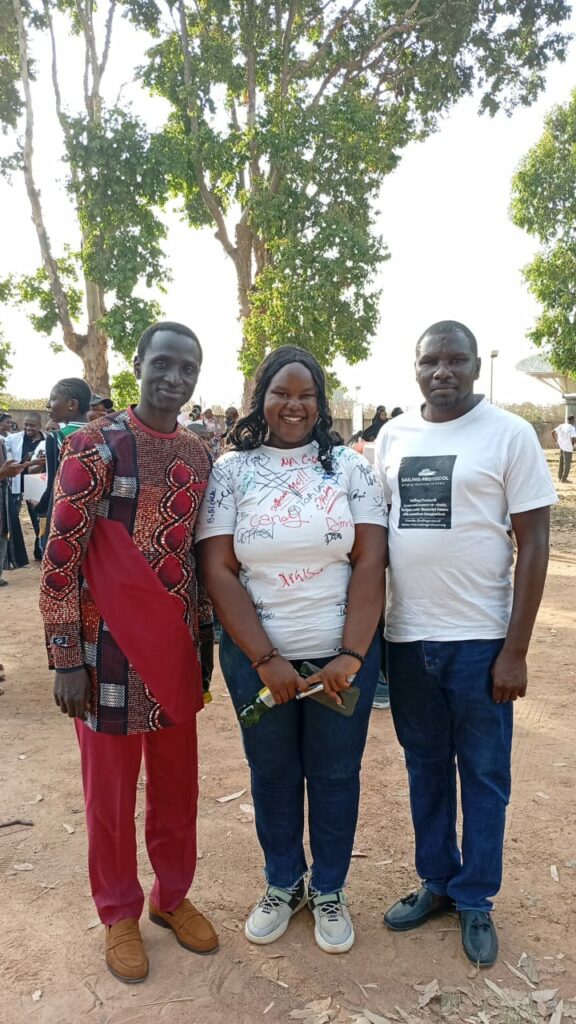

Grace Ali who is one of the beneficiaries of La Iris Human Development Initiatives just graduated as a Production student of the prestigious NTA college Jos Plateau State. We went to celebrate with her. Myself and Pastor Isuwa Mutah who is the Awareness Officer of the Organisation.

This is our Executive director Rev. Mancha Darong in a group photograph after receiving a training by UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) at BON Hotel Asokoro Abuja.

The training which drew participants from the Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Defense, Chief judges of the various states affected was loadable. The theme that year was “Children Recruitment and Exploited by Terrorist and Violent Extremist Groups: The Role of the Justice System

Advocacy Visit to His Excellency, Governor Calep Mutfwang for the rehabilitation, reconstruction, revitalisation, restitution and rebuilding of the Middle belt region. The visit was led

by Prince Chuwang Rwang who is also the Head of the coalition.

Our Executive Director of LA – IRIS Human Development Initiatives is the secretary of the Coalition.

Seven ( 7) states are involve in the coalition:

Plateau, Southern Kaduna, Benue, Taraba, Niger, Kogi and Kwara state.

Other places included are Southern Borno, Southern Adamawa, Southern Gombe and Southern Bauchi.

To God be the Glory.